B L N F S H D T C M G P R A O U E I

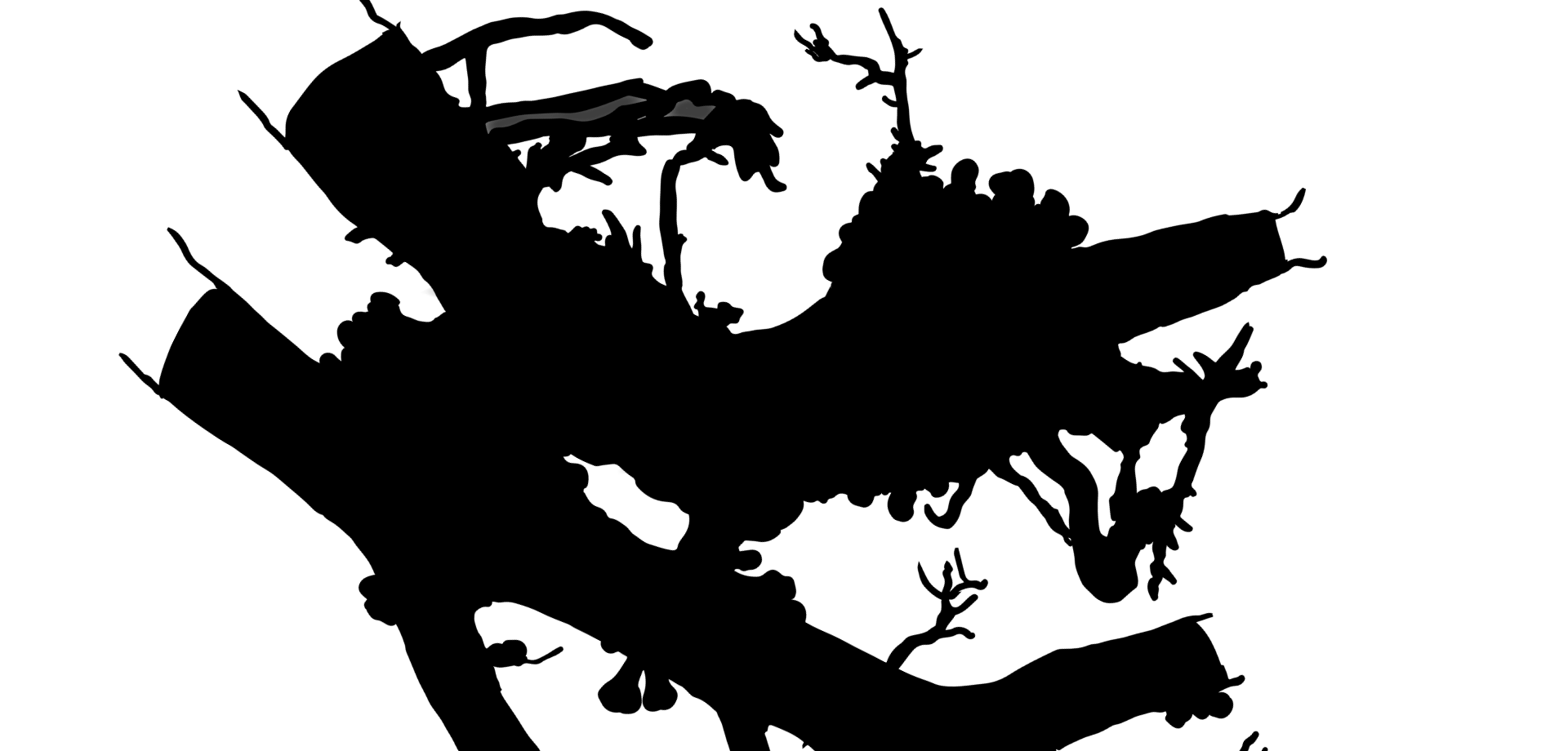

Like willow, alder lives by rivers, lakes and likes wet places. Sometimes gnarled and short on their own, together they will shoot up high, allowing many plants to grow around their roots, typically meadowsweet, ground elder and wild garlic. Attracting a wide variety of creatures, including insects, amphibians, water birds and small mammals and fish (since it is normally part of a shaded river bank), alders always create a healthy green space around them.

Alder bark was used to tan leather, its leaves for red dyes, flowers a green dye and its wood for charcoal production (to smelt iron, and in the past) for gunpowder. In spring its sticky twigs were made into brooms to catch remaining fleas (and its leaves will make horses tongues black). Rarely used for building (above water), since woodworm loves its protein-rich wood, its leaves and bark are antiseptic and used as a gargle to heal rashes and wounds. Medicinally, alder eases sore feet as its bark is a decoction for inflammation, while in homoeopathy the bark tincture is used for skin and glands. Curiously, pigs will not eat them. It belongs to the birch family (betulaceae), with common alder (alnus glutinosa) its most usual form.

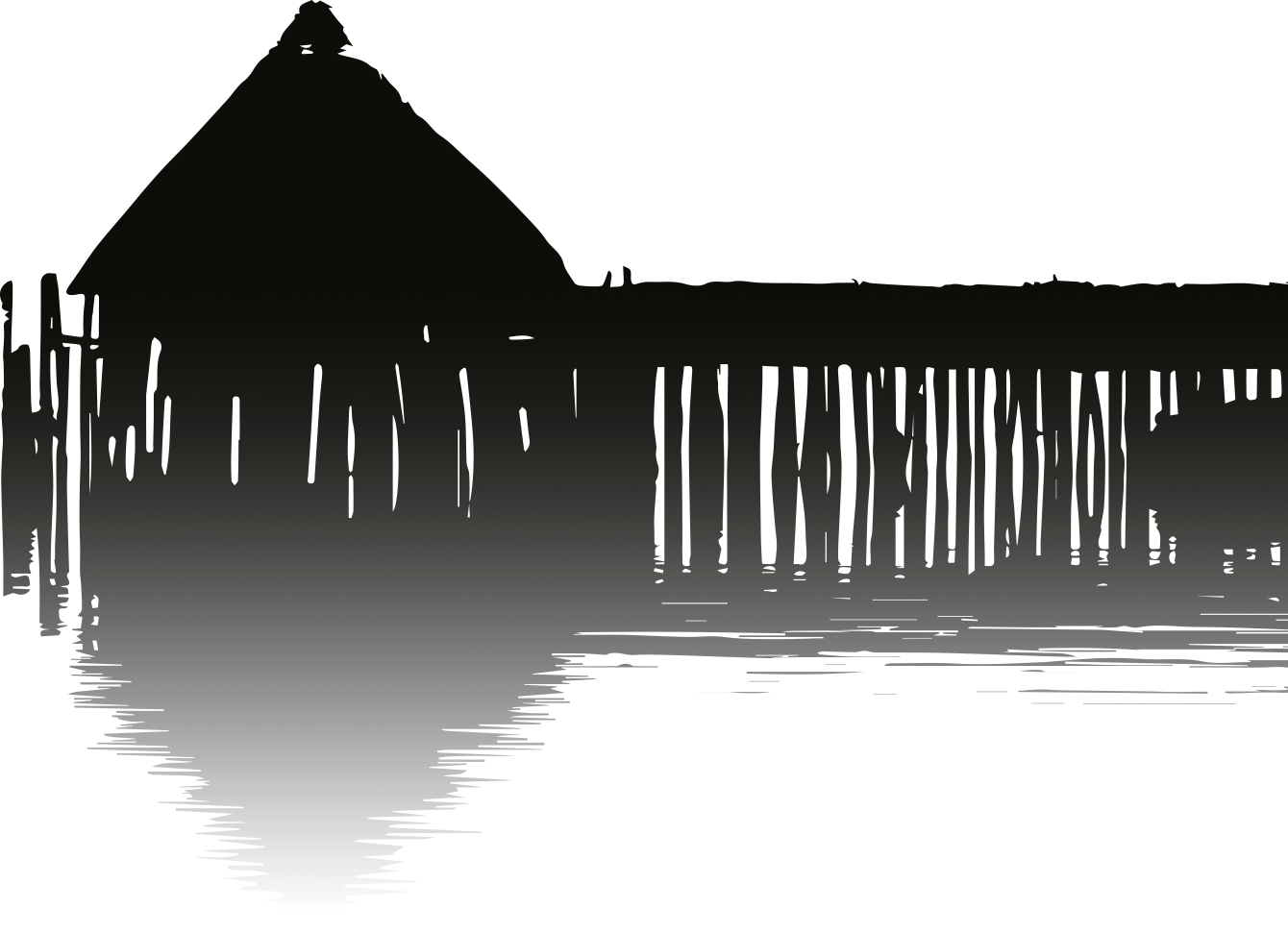

Because alder strengthens, drains and ventilates soil, it protects wetlands from becoming marshland. Alder has small horizontal sap pustules, and the freshly cut sap is orange-red, like blood. Most durable when constantly wet, alder wood has been in use for centuries to create bridges, pumps, sluices and piles (for causeways across marshes and to support buildings). Older still are the crannogs - built in Neolithic times.

Alder leaves appear after the flowers, and are sticky to begin with (hence its latin name glutinosa). The male catkins hang down like the birch (alder belongs to the birch family), while the female catkins mature into dark woody cones, sometimes called wattles, that often stay on the tree during the winter while the winged nutlets, using tiny air bags, fly or float away on the water to germinate downstream.

The answer to the old riddle of "what can no house ever contain?" was simply "the piles on which it is built". This refers to the fact that houses long ago depended on alder. Crannogs were built on alder piles and indeed ancient cities, including Venice. Bog alder or ‘scottish mahogany' is excellent for chairs due to long immersion in bog.

Alder roots grow deeply into wet ground, binding soggy soils that other trees cannot survive in because of a lack of oxygen. This binding protects river banks from eroding therefore, and the alder also achieves this by fixing nitrogen in its roots through a bacteria (frankia alni) that form large knots in the roots as well as from the air, which is why ground under alders is often covered in black leaves in autumn (a sign of nitrogen) when this mineral is given back to the plants around it.

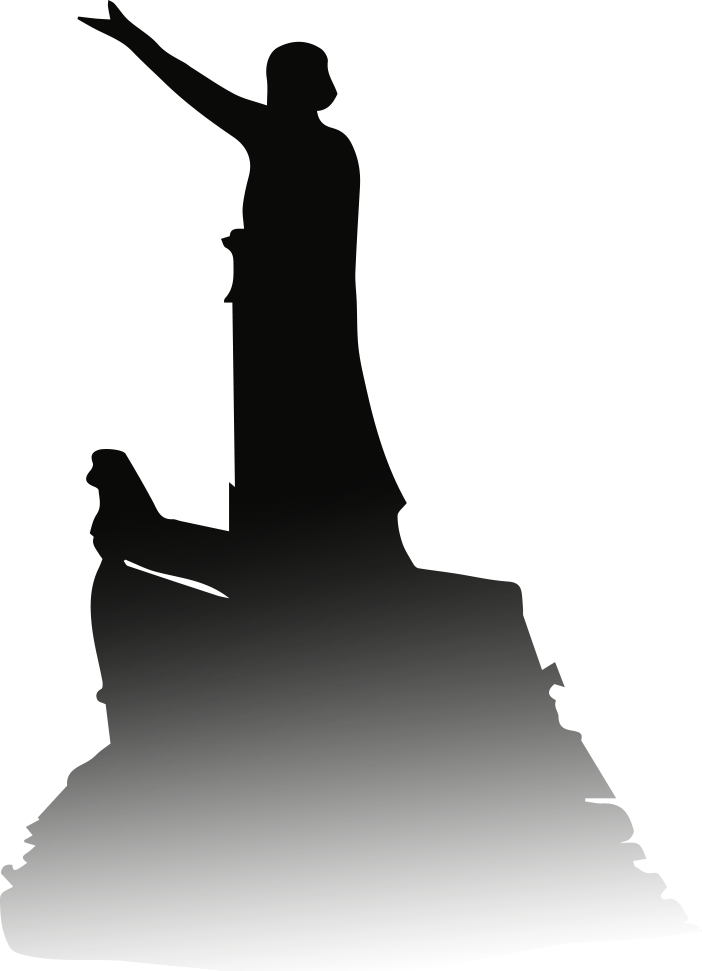

In one story, Bran gives his Cauldron of Rebirth to the Irish in connection with the marriage of his sister Branwen to the Irish king Matholwch, but problems follow. Bran then invades Ireland, wading the sea (he is too big for any boat), however, he is fatally wounded and his cauldron destroyed. Before dying, Bran tells his seven remaining comrades to cut off his head, and take it to Gwyn Fryn (the white hill) near London to face south. Bran's head then talks, sings and keeps them in blissful company for seven years, until the spell is accidentally broken. Nevertheless, the companions bury the head of king Bran near the tower of London, and the ravens are still there where, according to legend, they still hold a magical protection for Britain.

In the welsh Mabinogion, the alder is the tree of the giant king Bran, the Blessed, (also known as Bendigeidfran), whose name means crow or raven.

Living in wet marshy areas, alder is often seen as an imaginative creature of the mist and twilight in a world in which people never feel entirely comfortable. The Avernii were a gaulish tribe of the alder, hinting at the rather hidden connection between alder, king Arthur and Avalon (from ubhal or apple) - an underground thread through many stories. Manannan MacLyr (MacLir) ‘king of waters’ and sea journeys (gave his name to Isle of Man). Another connection between singing and alder is Orpheus, whose name is possibly short for orephruoeis 'growing on the river bank'.

Other names of alder, such as else, elsa, elise, or the scandinavian els, elze (service tree), hint at a burial side of the tree, as does the island of Alyscamps on the Rhone, or the elusive Elysian Fields. And the story of Niamh (of the Golden Hair) who kept Ossin (Ossian) below the waves in the Land of Youth for many years, has similar connection between water, tree and blissful forgetfulness.

In the medieval german legend, the Wulfdietrich Saga, an alder woman appears to foolish wanderers and turns herself into a hairy, bark-like creature called Rough Else if they try to kiss her. She is a wild-looking woman of the woods, covered in hair, who, in another part of the story puts a spell on the hero eventually making him mad. He runs through the woods, living on herbs for six months, after which she takes him on a ship over the sea to another land where she is queen. Bathing herself in a magical well that washes away her rough skin, she becomes transformed into the beautiful Sigeminne (her name means victory of love). Part of a german oral tradition, recorded by minstrels since 1221, this theme of madness and becoming someone else in the wildwoods appears in many celtic tales. Suibhne (Sweeney) the king, is turned into a mad owl in the Irish poem epic (inc Seamus Heaney's 'Sweeney Astray') and has to survive on watercress for many years, while the hunted Diarmid and Grainne, as well as Deirdre (of the Sorrows) who with the three sons of Uisneach, all hide in the alder swamps of Argyll during their flight from king Conchobar. The life-size wooden goddess (left) made of alder, dated between 728 and 524 BC, was found in a peat bog at Ballachulish, where she was sunk in a bog or lake, possibly as offering.